Exclusion and inclusion

What this means

Exclusion is hugely disempowering. There are all sorts of processes within health and social care that can exclude, from centralised decision-making that ignores or tokenises the voices of people with care and support needs, to physical buildings that sideline the needs of people with care and support needs. These issues can be further compounded by other structural inequalities, such as racism, ageism, sexism, homophobia and ableism. In order to share power, people need to be included. Looking at how and why people are excluded from power is the important step in sharing power as equals.

A lot of our discussions seem to boil down to exclusion. How people are excluded, and drawing up an action plan, or a route map, to change this.

What are some of the subtle ways power can manifest itself in social care?

Not being given clear and explained options, so denying people the ‘right’ to make informed choices/decisions. Information communicated in a way that makes little or no sense to people... Not being person-centred.

(Dean Thomas)

The research

When ‘exclusion’ is considered in the research, it’s most often accompanied by the word ‘social’. The focus of the existing research, therefore, is often on those who are excluded from infrastructure, communities, digital access, services, transport and so on; there is much less focus on exclusion from services’ own power structures and what services can do to address this.

However, the research on centralised and devolved decision-making structures, particularly when thinking about ‘localism’, is helpful. Localism is about giving voice, choice, and power to local communities – sharing power as equals with them – as distinct from a centralised, top-down model imposing decision-making from above.

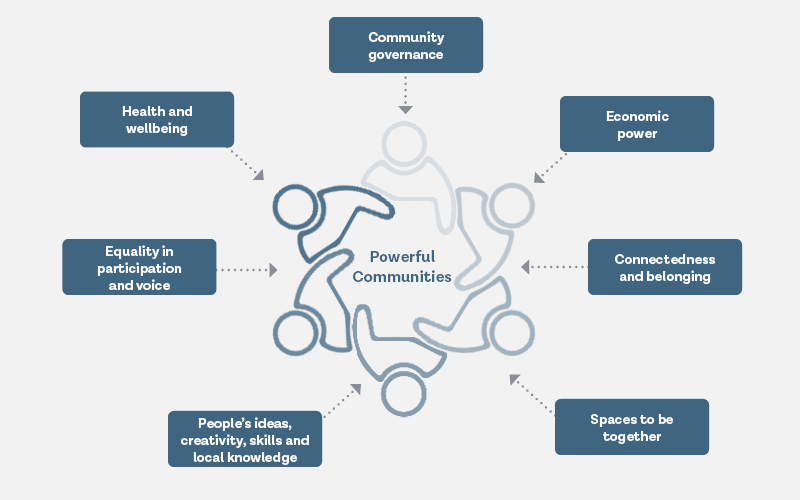

The Commission on the Future of Localism (2018) found that the ‘fundamental shift of power’ outlined in the Localism Act 2011 has not yet been achieved. It found that simply asking politicians and centralised bodies to give power away hasn’t worked. Instead, those currently in power need to support, harness and reflect the power of local communities in order to foster true inclusion. The diagram below breaks this down into all the different factors that need to be strengthened in local communities for true power-sharing to happen.

(Commission on the Future of Localism, 2018, p8: ‘What are the sources of community power?’)

When thinking about the commissioning of public services, Hitchcock et al. (2017) gathered evidence that ‘one-sized-fits-all services fail to respond to different needs, outcomes are not rewarded and services are sometimes duplicated or missing’ (p.5). This makes the point that when some people are excluded from power – in this case, commissioning decisions – it means those decisions are not likely to support equitable and cost-effective decision-making, and result in more fragmented services.

It's important, when considering greater power-sharing with communities, to pay attention to structural factors. Structural discrimination refers to macro-level exclusions that limit the opportunities, resources, power and wellbeing of individuals – this can be related to race, ethnicity, gender, disability, nationality, and other protected characteristics. Considering race and ethnicity, for example, there is increasing evidence that services need to go beyond a ‘colour-blind’ approach to one that embeds anti-racism over a more generalised cultural competence in order to foster greater inclusion (Chipawe Cane & Tedam, 2022; Tedam, 2022).

The Sharing Power as Equals group also wished to emphasise that carers, including young people who held caring responsibilities, were often excluded from discussions. There is more information on this in the More Resources, Better Used section on Valuing Family and Unpaid Carers.

What you can do

If you are in senior management: The Sharing Power as Equals group agreed that (to paraphrase George Bernard Shaw) “…all progress is through unreasonable people.” This means that things change when people make a fuss, speak up, and say things that people may not want to hear. Therefore, actively seeking out opinions from those currently excluded from power, taking them seriously, even – and perhaps especially – if they feel uncomfortable hearing the opinions, is vital. Otherwise effective change will be less likely.

Devolve power to the lowest point where the issue can be solved, the group said, because so many resources are wasted by not having faith in people. Ask yourself:

- What decisions are already devolved or co-produced? What made this a success, and what were the challenges? How were those challenges addressed, and what can be learned?

- What decisions can you immediately devolve to (or, at least, co-produce with) people who have care and support needs?

- What decisions are left – and how can you work towards devolving or co-producing these, too?

How can you create an action plan, with clear routemaps and timescales, to increase the delegation and devolution of decision-making? You may find it helpful to consider the diagram above, thinking about how each of these aspects of community power can be strengthened.

If you are in direct practice: You can consider similar questions in terms of the work you do with people. Ask yourself:

- How do you practice the principle ‘Nothing about us, without us’ in the work you do with people?

- What gets in the way of this principle in practice – and who can you challenge about this?

- How can you share successes in practising this principle, and support others?

You may find the publication and podcast Risk, rights, values and ethics, and the section The social model of disability in Leading The Lives We Want To Live, useful as you consider these questions.

Further information

Watch and listen

Wayne Reid, BASW England’s Professional Officer, shares his work on anti-racism in social work in this video and this podcast.

Read

The ‘Plain English’ guide to the Localism Act 2011.